Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/Aditi Phadnis & P Vaidyanathan

August 05, 2004

It was a small political gaffe but a revealing one. On July 15 a thatched roof caught fire in a school building in Kumbakonam and around 90 toddlers perished in the blaze.

In faraway Delhi the Prime Minister's Office scrambled into action and ordered Telecom Minister Dayanidhi Maran to the spot instantly.

What did the prime minister's men do wrong? Shouldn't they have sent Kumbakonam MP Mani Shankar Aiyar (his Mayiladuthurai constituency includes Kumbakonam) for the symbolic visit to the disaster site?

Wasn't this a demonstration of how the Prime Minister's Office lacks political nous? Manmohan Singh certainly thought something had gone wrong.

The next day he flew into a temper about being given the wrong advice. "Anyone who thought the PM was a soft-spoken man changed his mind the next morning," says one bureaucrat.

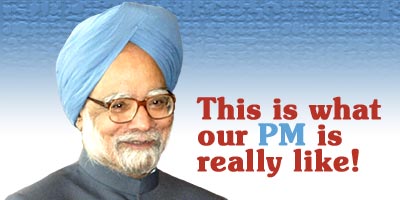

It has been 71 days (on July 31) since Manmohan Singh made the unexpected ascent to the country's top job. During that time he has emerged as the most low-profile prime minister the country has ever had.

He has made one trip to Andhra Pradesh, a key Congress bastion, and another to Assam from where he has been elected to the Rajya Sabha. Last week he made his first trip abroad to Bangkok, for a meeting on regional trade and cooperation.

His advisors talk about long hours in the office, of a man who is poring through the files that the system throws up to him. Perhaps that's why some insiders say he is less dependent on his principal secretary than any other prime minister has ever been. "He's a hands on man. Be it foreign affairs, the economy, rural development or water, he likes to take a first account from the concerned secretary," says a senior bureaucrat.

Unlike most prime ministers his routine has -- so far -- been fairly fixed. It starts around 8.30 am when he meets a stream of relatives and family friends at his home on Safdarjang Road. The scene then shifts and by 9 am he's at Race Course Road where he meets party workers and political visitors, like chief ministers who usually come with requests for large dollops of cash.

By 10, 10.30 am he's behind his desk in South Block. It's a desk that stays clean throughout the day. There is no computer because Singh is still a pen and paper man. "He does not belong to the Naidu generation and still uses long hand," says an aide.

Inevitably, the day begins with a comprehensive briefing from a small, closely-knit group of bureaucrats. The key players round the PM's desk are seasoned hands: Principal Secretary T K A Nair, National Security Advisor J N Dixit and Special Advisor M K Narayanan. That's followed by a media briefing about the top stories of the day.

If Parliament is in session the briefings are usually held in the prime minister's chamber in Parliament House. For the next hour Singh has 'quiet' interactions with people who he needs to meet. On most days he meets about a dozen people but most are usually kept short.

He has been busy filling what he regards as gaps in his education. So, he has been calling in the files on subjects like foreign affairs which he had never focused on earlier. "Earlier, in his career, he never really focused on foreign affairs, defence and nuclear issues. So, he had to spend a lot of time just getting briefed on them," says an official.

Also, he believes that subjects like rural development and water resources are of paramount importance, and has called in the respective secretaries to get a bird's eye view of the fields.

Manmohan Singh isn't young so, when he's in Delhi, he likes to follow a structured routine. He takes a long two-hour lunch break from 1.30 pm to 3.30 pm when he goes home. Because he eats a light breakfast his physician insists that lunch must be promptly at 1.30 pm.

On one occasion during the Budget discussions the doctor broke up a meeting at 2.15pm saying it was time for lunch. Says a PMO official: "His doctor had to step in and ask him to continue after having his lunch."

In the afternoon the scene shifts back to Race Course Road. Here, he still has to deal with India's intractable problems, but he does have a lovely view of the manicured lawn and the resident peacocks.

Considering that Manmohan Singh has India's woes on his table every day, it's hardly surprising that he works long hours. His working day usually stretches on for about 12 hours and at times it even goes on for 15.

One night, for instance, he was being briefed on the situation in the north-east till 10.30 pm and the next morning he took off at 7.15 am for a flight to Assam.

The day before the Singapore prime minister arrived, he was being briefed till 11.30 at night on issues relating to the free trade agreement with that island economy. International visitors have usually been impressed with his sincerity and affability, and his detailed knowledge of issues.

The workload is even more arduous because so far he has wanted to go through all the files in detail-to the point where aides advise him to meet people a little more, and spend less time on the files. But he's determined to master it all himself.

That showed during the Budget when -- not surprisingly -- he was eager to be kept in the loop about Finance Minister P Chidambaram's economic blueprint for the nation. "Chidambaram may not have liked being called so often. But, the reality is that Singh did not want anything to go wrong in the new government's first economic statement," says one senior official.

Manmohan Singh and Chidambaram met to discuss the Budget six times and at least three of these discussions were lengthy ones. But, contrary to some reports, Singh did not go into the taxation details. "Singh's interest was largely restricted to policy issues. He was very concerned that the issues highlighted in the Common Minimum Programme be

adequately reflected in the Budget," says an official.

The decision to hike the FDI ceiling in insurance was taken during a closed-door session between Chidambaram and Singh. "It was decided during the last day or two. They knew the Left parties would oppose the move tooth and nail, but they banked on the NDA to support the amendment to the Insurance Act," says a source.

And when the Left kept up its vociferous opposition, Singh erupted at a morning meeting in his office, and said that if they thought he was going to cave in, they were mistaken.

Still, the operative word for Manmohan Singh is 'low-key.' That was reinforced over the weekend when he issued orders banning the airport darbar that always takes place when Indian prime ministers take off for foreign shores.

Interestingly, his orders were ignored and even Congress President Sonia Gandhi turned up at Safdarjang airport before he climbed on board a helicopter to Palam. Once on the way to Bangkok he held an impromptu press conference that was surprisingly informal.

Meet Dr Singh: The Complete Coverage

Being low profile and approachable is one thing. The more important issue is what kind of difference Manmohan Singh will make to the country. He has moved into office when the economic situation is taking a turn for the worse (on account of the failed monsoon), when the security situation is not what it was ("Pakistan is up to no good", said an aide), and when in the world of politics the BJP is looking for every opportunity to embarrass the government.

But Singh wants to tackle every issue in depth. He sent an aide to Vajpayee to find out what kind of road map his predecessor had for the peace talks with Pakistan, and found there was none. "Give me the options, then," he told Dixit.

On the free trade issues, he felt proper homework had not been done, on whether the agreements with South East Asian countries were really in India's interest. So he has ordered detailed studies on that as well.

And on the CMP's main promises, he is relying on Montek Singh at the Planning Commission to get the home work done. At his first meeting with the Commission's new members, he spent three hours going into the details of development programmes, and advised the members to speak their mind even if they disagreed with the government.

Still, those who saw him at a meeting with the Editors Guild came away with the sense of a prime minister who is even now getting to grips with issues and formulating policies and responses. Asked why he was working such long hours, he replied with typical modesty: "I'm a slow learner." In answer to a question, he reminded his interlocutor: "I have been here

only two months."

His aides say he is a good boss but a demanding one. But the million dollar question that every political analyst is asking is about how much power Manmohan Singh is free to exercise.

Is he constantly looking over his shoulder to check what Sonia Gandhi thinks of his every move? There are rumblings beneath the surface that he's unhappy because External Affairs Minister Natwar Singh has been bypassing him and briefing Sonia about his talks in Pakistan. And, on the Shibu Soren crisis Defence Minister Pranab Mukherjee was the key negotiator and he once again reported directly to Sonia.

And what happened when Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh decided to take the law into his own hands and cancel the agreement on sharing river waters? When Amarinder moved quietly, it seemed that neither Manmohan Singh nor Sonia Gandhi was calling the shots.

Was that because there was an information gap between them? Insiders admit that the PMO and the home ministry heard about Amarinder Singh's moves from the television. The PMO till late in the evening was convinced that only a harmless resolution was being passed in the Assembly, not a law.

Amarinder Singh's attitude when he finally met the prime minister was obdurate. Says one official: "He (Amrinder Singh) was totally defiant. The signal he sent at the meeting was: "I can't do anything about it."

Did Sonia Gandhi know about Amarinder Singh's moves? One explanation is that she failed to grasp the significance of his moves. And have Manmohan Singh and Sonia talked in detail about the crisis?

That again returns to the question about his relations with Sonia. The original gameplan was that the two would meet every Saturday. But Singh has been busy firefighting and so far there have been only two such meetings.

"Their relationship is not one of friendship. There is scope of misunderstanding, although given the personality of the two leaders, this threat can be said to be minimal," says one minister. Most importantly it seems that the prime minister can just pick up the phone any time and have a quick chat with her.

But Sonia doesn't like taking instant decisions. If the PMO sends her a query she also calls in her own team for consultations -- which slows down decision making.

One thing's for sure: Manmohan Singh isn't a Congressman in the traditional mould. The prime minister is reclusive, defensive and "has never done anything for anyone in his whole life," said a disappointed Congress functionary who was expecting to get a PMO post (the PM told him that as they were both from the same community, it would not be right to hire him). The average Congressman learns quickly that it pays to be politically flexible. Manmohan Singh is anything but flexible.

There's a story told by a wealthy MP from Haryana who has large mining interests in the state and who was an AICC office-bearer. The MP dropped in one morning at the prime minister's Safdarjung Road home and, afterwards, spotted Manmohan Singh's driver.

He walked up to the driver and introducing himself, slipped two new Rs 500 notes in the driver's breast pocket. "You must be running up expenses on chai-pani. This is for you. You people have to work so hard" he said, patting the driver on the shoulder.

Within a few hours Dr Singh's driver reached the MP's residence. Handing the MP an envelope he said: "Saab wants you to call him." The MP made the call. "My driver has something to return to you. Please don't come to my house again," said Dr Singh icily. The MP tried to explain that it was just a gesture of Haryanvi courtesy. "I don't want to discuss it" said Singh and put the phone down. The envelope contained the Rs 500 notes.

One thing's for sure: Manmohan Singh is as different from A B Vajpayee as chalk is from cheese. He wants the detail (a 40-page memo on a complicated subject was welcomed and devoured -- which no one since Indira Gandhi would have done); he wants the total picture before making a move; and he wants to address the most difficult issues of development, not just make the flamboyant gesture or announce a grand scheme.

It's a harder road to walk, and it does not help that he runs a minority government with multiple handicaps. A decade ago Finance Minister Manmohan Singh put his indelible stamp on modern India. The jury is still out on whether Prime Minister Singh will be able to put a similar stamp on 21st century India.

Powered by

Photograph: PORNCHAI KITTIWONGSAKUL/AFP/Getty Images

Image: Uday Kuckian