Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/Tara Shankar Sahay

March 30, 2004

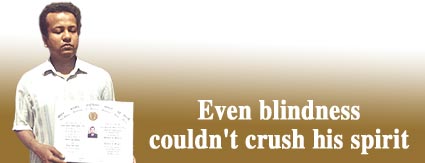

Jharkhand's scheduled tribes nervously await a gutsy local youth who left several years ago to become a doctor and returns with his dream fulfilled after overcoming a decade of harassment and official indifference and paying a heavy price -- the loss of his eyesight.

When C S P Anka Toppo left Ranchi way back in 1989, little did he know that his tryst with destiny would include blindness and victimisation at the hands of those who kept putting up obstacles in his path.

But the tribulations only hardened Toppo's resolve to become the first blind person in India to procure a medical degree from the prestigious All-India Institute of Medical Sciences.

Today, having earned an MBBS degree after 14 years of toil, the soft-spoken Toppo feels no rancour towards his erstwhile tormentors. "He exemplifies what is generally referred to as the triumph of the human spirit over adversities of the worst kind," said senior Supreme Court advocate Sadhana Ramachandran, also a human rights activist.

Toppo's tale proves how a brush with authority, even for a blind medical student, can result in consistent vindictiveness designed to defeat, demoralise, and destroy a persistent personality.

When Reuben Toppo's son left Ranchi to pursue medical studies in Delhi, life held a lot of promise. He cleared the first and second professional exams and was poised to take the final one when disaster struck.

When Reuben Toppo's son left Ranchi to pursue medical studies in Delhi, life held a lot of promise. He cleared the first and second professional exams and was poised to take the final one when disaster struck.

"There was some problem with my eyes in 1993 and so I went to hospital," Toppo told rediff.com "I was told I would have to take medicines and I did. But after initial improvement, my vision deteriorated."

The problem was far more serious than earlier thought. Toppo underwent as many as five operations after two years of treatment. But it was all in vain. Slowly but surely, the light dimmed and went out. The verdict: he was afflicted with Eale's disease, a one-in-a-million case.

"I was told that restoration of my eyesight was difficult," he recalled. "It was an understatement."

The young man was now confronted with a peculiar problem. "I wanted to be a doctor, but I was blind!"

But he also knew that the aspirations of his community -- he is now the first doctor from among the scheduled tribes in Jharkhand -- rested on his determination to succeed.

"I overcame my dread slowly," Toppo said, "and gained courage to complete the course. I heard about the reading machine used by blind people, which converts printed books into speech, and appealed to friends for help. In those days, use of the Internet was uncommon, but I came to know that I could read books through a computer scanner."

The AIIMS Students Union stepped foward to help Toppo buy a computer and a few friends informed him about the National Association of the Blind, which imparts training in the use of computers. "I got invaluable training there," he said. "I got some medical books scanned and some recorded. Then I began preparing for the exams."

But it was not so easy. When Toppo approached the Institute for permission to take the exam, he was told that there was a problem. The Medical Council of India opposed his entry. No reason was assigned.

"But I was not disheartened," Toppo continued, "because in a similar case in Bangalore, a blind student had been granted permission to appear for the MBBS exams with the help of an assistant. But I couldn't understand why the MCI had not given me permission."

With help from friends like advocate Sadhana, Toppo discovered that 25 years ago, Y G Parameshwarappa, a student of Bangalore Medical College, had become visually impaired in the fifth year of the MBBS course. "But Parameshwarappa was allowed to give the exam with the help of an assistant and he earned his medical degree. Today, he is a professor in the college's department of pharmacology."

With help from friends like advocate Sadhana, Toppo discovered that 25 years ago, Y G Parameshwarappa, a student of Bangalore Medical College, had become visually impaired in the fifth year of the MBBS course. "But Parameshwarappa was allowed to give the exam with the help of an assistant and he earned his medical degree. Today, he is a professor in the college's department of pharmacology."

In October 1999, Toppo again applied for the final exam, but was stopped midway. The authorities argued that he would have to await the MCI's permission. Toppo was even forced to leave the examination hall.

"I don't blame the [AIIMS] faculty," Toppo said. "My information is that during a meeting of the deans it was discussed that I couldn't be stopped from taking the exams and some said I should be permitted. But the MCI had its own thinking."

Toppo, however, had reached the limits of his patience. He could not stand the mental torture anymore and approached the National Human Rights Commission for redressal.

The NHRC was then headed by former chief justice of India Jagdish Sharan Verma. Justice Verma summoned then AIIMS director Dr P K Dave to discuss the matter.

Toppo was also called in by the NHRC for counselling, but the AIIMS took the stand that as the MCI was disinclined to let him take the final exam, he would have to make do with a bachelor's degree in human biology.

"I reasoned with them [the AIIMS] that there was a precedent in Bangalore," said Toppo, "but they kept asking whether the precedent occurred in the AIIMS! They were pushing me into a heads-I-win-tails-you-lose situation. I kept quiet."

Toppo wrote a polite letter to the AIIMS authorities requesting them to give their stand in writing, so that he could respond to it. Nothing came from the institute. On the contrary, it kept reminding him that he had not replied to the counselling. Toppo told the NHRC that his only request was that any proposal to him be made in writing.

In March 2001, the NHRC summoned both Toppo and the AIIMS authorities to resolve the tangle. A video was played showing the Parameshwarappa precedent in Bangalore. Justice Verma asked why Toppo's case could not be similarly resolved. Dr Dave replied that he would look into the matter. But more hairsplitting followed.

Justice Verma, who became a household name when he headed the bench that oversaw the investigation of the sensational hawala [illegal foreign exchange channel] scandal in the mid-1990s, then put his foot down and insisted that the case could no more be swept under the carpet.

The AIIMS responded that there remained some impediments. But Justice Verma would have none of it. If there are impediments, remove them, he told the AIIMS.

Justice Verma's successor in the NHRC, former chief justice of India Dr Adarsh Sein Anand, told rediff.com, "The Commission has taken the rights of the disabled as a matter of grave concern. The focus must shift from mere welfare to the rights of the disabled. The AIIMS was misreading the Supreme Court judgment [pertaining to these rights]."