Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/Ramananda Sengupta in Mumbai

February 12, 2005

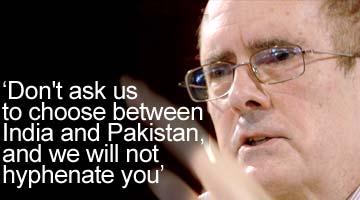

"Don't ask us to choose between India and Pakistan, and we will not hyphenate you."

That was the deal former US deputy secretary of state Strobe Talbott offered the audience at the Mumbai University auditorium on February 10. He was responding to a question on why the US continued to support Pakistan despite its record on nuclear proliferation and terrorism.

Earlier, Talbott, the president of the Brookings Institution, who was invited by the Observer Research Foundation -- which recently tied up with Brookings -- made an erudite presentation on Indo-US relations and whether the nations were natural allies.

"What are natural allies?" he asked. "Soldiers know it means we fight on the same side. But the large political question is, what does it mean to be on the same side? My president [George W Bush [Images]] would say, we are on the same side on the war on terrorism. The formulation, that if you are not with us, you are against us, is what he used to deal with the general, President Pervez Musharraf [Images] in Pakistan.

"Recently, he put forward another answer. He says we are on the same side with respect to democracy and freedom. Lord knows that was the theme of the inaugural address.

"It is unmistakably true that these are worthy causes. Terrorism is an absolute evil. We should all be against it. Freedom and democracy are good. We should all be for it," said Talbott.

"There's no question we are on the same side. India and US were attacked by terrorism within 100 days of each other, in the fall of 2001. Clearly, we are on the same side. As per the clich�, which happens to be true, we are the world's oldest democracy, and you are the world's largest democracy. We are on the same side there.

'Nonetheless, I don't think either of these answers quite works as far as explaining the meaning of natural allies.

"The problem with terror is that first of all, it is not an 'ism', it is an instrument available to any of an array of political causes. Therefore, the very concept of a war on terrorism, in the space of four or five syllables, has two fallacies: One is, it is something you can make war against, like you can make a war against a country or an alliance. The other is that it is an 'ism'. Neither is true," said Talbott, who was the point man for dealing with India after its nuclear tests of May 1998.

"If you say the war on terror is a unifying principle, it puts us in the US in the position of having to tolerate, and endorse, more than we should, the regime in Uzbekistan, which uses the war on terrorism to justify grotesque abuse of human rights.

"It has made President Bush less inclined than he should be to speak out about the way in which President Vladimir Putin [Images] in Russia [Images] has used the war on terror as a rationale to conduct what amounts to atrocities in Chechnya.

"'With regard to freedom, it is a little tricky. It puts us on the horns of a dilemma of being inconsistent in our policies. If we are for freedom and democracy, if that is the litmus test we will apply to nations with which we have good relations, how do we justify relations with China, which the last time I checked was Communist? Saudi Arabia, which is an antique monarchy? Pakistan?

"The answer is, there are sound reasons in each case why the US should have solid working relations with the countries. It certainly isn't a shared commitment to democracy."

He said the answer has something to do with globalisation. "There are groups in both nations against globalisation. I don't think globalisation is something you are for or against, good or bad. It is simply a fact of life. It is something to be managed.

"The challenge it seems to me, is to ensure the benefits of globalisation overshadow the dangerous aspects."

In a very "gross approximation, there are about six billion people in this world, which is roughly divided 50-50 between those who feel themselves to be winners or beneficiaries of the process of globalisation, and those who feel they are losing out to globalisation.

'That's not a healthy ratio. It is worse when you imagine the ratio shifting in the direction of the losers because of unsustainable population growth in parts of the world that are very, very poor.

"The overwhelming objective of mankind should be ensure the gap between winners and losers is narrowed rather than widened," he said, since otherwise, the losers will "literally take up arms".

On the US being the sole superpower, he said, "Presumably our superpower relationship is based on three things, not necessarily in that order: Our all powerful military, the almighty dollar and the global appeal of American values.

"None of those are in great shape. Our military has got its hands full in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is not about to encourage using that power elsewhere unless it is absolutely avoidable.

"The dollar? Hello... you are all lucky enough to have rupees. When I got to Europe, I paid $100 for a taxi ride from Heathrow to my hotel. So much for the almighty dollar.

"As for American values, the very fact that you are asking the question suggest there are dents in American values around the world, and we Americans have a lot of tending to do.

"In physics, there is no such thing as unipolarity. There is no such thing as multi-polarity. There's only bipolarity.

'If we use the metaphor, we ought to stay with good physics. Good physics says it is no longer a bipolar world. I don't know what that means, but it is certainly not a unipolar world.

"If it was, Americans would do what many Indians accuse us of doing but we cannot do, which is reordering the world the way we want it to be. You have seen us in recent years trying to do that. We have not been able to do it.

"It will come as great relief to you, I am sure, but there are some things, if we were really running the world, which you would not want us to do. Including in your neighbourhood."

On what the US was willing to give up to augment US-India relations, he asked, "I don't know, what do you want us to give up. I suspect some people involved in security studies would say give up the last vestiges of the Nuclear Suppliers Group and restrictions on sensitive commerce and cooperation that resulted from India's decision to be nuclear weapons state outside the NPT.

"I would argue that we cannot, we should not, and that you should not ask us to. Instead, you should work together with us to find a way to reconcile India's position outside the NPT with a strengthened NPT.

"Other than that, you tell us what we want to go give up, and I will tell you why we won't," he said amid laughter. .

"I would cautiously predict the new US government will not be as unilateralist, and that isn't because personalities have changed, although there have been some changes," he continued.

"President Bush is a pragmatist as well as a politician. He knows he has his hands full in Iraq and in Afghanistan. He does not need to take on another war and another occupation, not to mention several wars in the second term.

"He knows he has a major economic challenge. It is significant that he has asked Vice President Dick Cheney to spend a lot more time on domestic issues... the budget deficit, social security and that kind of thing, and by implication, spend less time on foreign policy."

Returning to India and Pakistan, he said, "In this part of the world, when you said F-16, it was mentioned solely in the context of Pakistan, planes that we were selling and not delivering to Pakistan.

"Now I see F-16s are in some sense under consideration by your defence acquisition authorities. That in itself presents a dehyphenisation of the triangular relationship. Much of what you say about Pakistan is true, yet you overlook a couple of things. Yes, Pakistan continues to be a non-proliferation problem rather a solution.

"A Q Khan, an individual, and a very very powerful individual, who has done a great deal of harm, was consigned, in some sense put into retirement. A lot of people think he should have put somewhere else, but during the Clinton administration, we tried like the dickens to try and get a handle on Khan. We could not get anything done about it.

"The Bush administration did, and that is to its credit. That Khan, at least, is out of business. It does not mean the problem as a whole has been fixed. The US government is working on that, including through the leverage that comes from our military-to-military relationship with Pakistan.

"You tend to discount the significance of the reversal in decades of Pakistani policy that the Bush administration was able to bring about post 9/11 with regard to Afghanistan. The Taliban regime, directly and the Al Qaeda [Images], indirectly were largely a creature of the ISI and the Pakistan authorities. They were also a Frankenstein's monster created by the US through its proxy war in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union in the 1980s. It is another chapter of the story we Americans have to recognise. But the Bush administration has, by taking the position that you are either with us or against us, got a reversal of Pakistani policy. That is significant.

"What is even more important is that quietly, American officials are very clear with Pakistan that it must stop the export of insurgency and terrorism in other directions, into India and Kashmir. I am not saying they have succeeded entirely in that, but it continues to be very important part of our policy.

"Let us make a deal: we won't hyphenate you, if you don't force us to choose between India and Pakistan. It should never be the strategy of India to say, 'Okay, US, make a choice, it is either those guys or us.' We will not make that choice. You are not going to get Americans to say it.

"In my book [Engaging India: Diplomacy, Democracy and the Bomb], I wrote about dialogue with then external affairs minister Jaswant Singh. My regard for him knows no bounds. But I have strong disagreements with Singh. He was the most eloquent advocate imaginable of the view that the US should make a clean break with Pakistan, treat Pakistan as a failed state, as a rogue state, a talibanised state, to write it off, and put all of its chips with India.

"I basically said, no, Jaswant, and here's why. Read my book. There, maybe I've sold a book or two," he joked.

'Don't ask us to make a choice when India itself is greatly improving its relations with Pakistan. Count on us to do everything we can to work with Pakistanis to ensure they don't screw it up, the way they did in Kargil," he concluded.