Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/Amberish K Diwanji at Waltangu Nar, Kashmir

February 25, 2005

You walk on the roof of a house but you don't realise it; it feels more like a snow-covered path.

That is the impact that the two avalanches that struck the village of Waltangu Nar, a settlement of Gujjars a two-hour walk up the mountains from the main Waltangu village, on February 20, have had.

Of some 100-odd houses in the village, less than a dozen are visible and intact. The rest have either crumbled or lie buried.

Signs of devastation are all around. A house lies, caved in and buried. Of the 12 members inside, only one has survived.

Ghulam [Images] Hasan Tenda is distraught. He has lost his entire family. "That day seemed okay. It was bright and snowing as it has been over the past few days. Suddenly I heard this noise and saw this wall of snow descend. It buried the village," he recalls.

Then came the second avalanche, from another slope.

Waltangu Nar is like so many settlements: it has no electricity, no water, no road leading up to it. In fact, the entire village comes under the BPL (Below Poverty Line) scheme. After the avalanches, the victims were unable to inform the neighbouring villagers. And even if they could, in the evening, little could be done. As night set in, the devastated villagers had no option but to remain in the village, fearful of another avalanche.

Moreover, one had some chance of surviving inside a house, but none out in the open.

The day after the disaster, people from the neighbouring villages walked up to lend a hand. They began the painful task of clearing the 10-feet deep snow, making first a road and then pathways.

From some of the huts emerged survivors and the bodies of the dead. Since Islam mandates that the dead should be buried as soon as possible, the villagers went about arranging the final rites.

Since actual burial is out of question given the huge pile of snow and hard ice on the ground, the villagers simply placed the dead inside the caved-in huts and covered them with the debris and snow. A proper burial will be in the summer, they say.

No one is sure about the toll. So far, reports say it is at around 250, and climbing. Volunteers are slowly trying to uncover each and every house that made up Waltungu Nar, starting from the lower slopes. They insist that higher up, there remain more houses waiting to be dug out. The desperation is evident: every passing day increases the likelihood of death.

"It will take more than seven days to uncover all the houses," says Mohammad Jabbar Butt, a resident of Waltangu. He says he was among the first batch to reach the Gujjar settlement. Besides the dead, according to him, there are many who are missing.

The avalanches struck in the afternoon, a time when many people are outdoors, attending to their chores or simply enjoying themselves.

"We will only know the final toll in the summer, once the snow melts and clears away," says Butt.

At Waltangu Nar, there is anger against the government for its abysmal failure to respond speedily. In fact, the tragedy is that not only did the government respond terribly slowly, it appeared to be a hurdle in the way of those seeking to do some work.

"When we villagers could go up, why could not the police and the army?" asks Butt. "One can understand that the army has its limitations since they are here to keep a lookout for militants (a truth brought home after militants carried out attacks in Srinagar [Images]), but what about the others?"

The villagers ask why the army or the administration could not set up a couple of tents and keep personnel inside, available 24 hours.

Not that everyone disappears by evening. A team of doctors and paramedics have been camping at the site since Monday. "Please let the world know that we have been here and are doing our job," one doctor says.

Rajvalali, a Gujjar, has mixed feelings. His family is safe, but he has lost his two brothers and their families. Theirs was a cluster of three huts; his brothers' huts bore the brunt of the avalanches and caved in while his own stood.

"We are poor folks here, just herders of cattle. Which is why the government really does not care for us," he complains.

Mohammad Hasan was dug out of the snow after being buried for three days. In his large hut lived 17 members. When they heard the avalanche coming, they all fled inside. But the hut was not able to completely withstand the snow. Part of it caved in, killing his wife and two sons, beside the families of his brother. "I wish I too had died," he says.

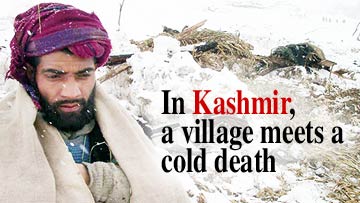

Photograph: Qayoom Wani | Headline Image: Uday Kuckian | Man in the Image: Abdul Gani Deedat